As children, we are warned to steer clear of addictive influences. But I can blame my eventual affliction on something on the shelves in my family’s library, two doors down from my room: a book of fairy tales by Hans Christian Anderson.

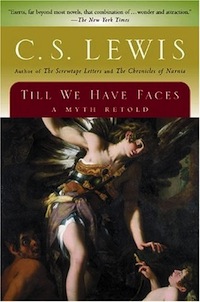

Much of my reading as a child was unsupervised. At night, my grandparents slept two floors above, innocent of my night childhood insomnia. The spine read Fairy Tales, but inside, the stories weren’t like anything I’d been read before bedtime. The endings to Christian Andersen’s signature stories, ranged from the merely unjust to the downright macabre. How could I avoid dreaming adaptations and futures for swan princes and mermaids? My addiction to reshaping narratives has comprised a large part of my writing for many years. But perhaps no other retelling cemented the sort of stories I wanted to write than C.S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces, a retelling of the Psyche and Eros myth.

The original story all starts with a jealous Venus. After hearing Psyche’s beauty rivals her own, Venus dispatches her son Eros with his famous arrows to entrap Psyche into falling in love with something ugly, monstrous, or, better yet, both. When Psyche’s parents discover her intended is a beastie, they bid her adieu. Deposited on top of a mountain, Psyche is not greeted by a monster, but by an unseen Eros who has clumsily scratched himself with one of his own arrows and fallen truly, madly, deeply in love with Psyche.

Eros remains hidden, keeping Psyche in deluxe accommodations. Chartruese with envy, Psyche’s sisters demand she shed light on her beastly husband. Duped into their awful plan, Psyche discovers a mate whose beauty rivals her own. But uncovering him, she burns him with the oil from her lamp. He wakes and flees. Alone, sorrowful, and heartbroken, Psyche wanders until eventual tasks of fidelity allow her to be reunited with her love.

Though iterations of the story have been retold for centuries—from folktales such as East of the Sun West of the Moon (beautifully retold by Edith Pattou in the lush YA East) to fairy tales like Beauty and the Beast—Lewis threw out romantic love for his exploration of the myth, and refocused the perspective from Pschye to one of her meddling sisters, whose actions Lewis was unable to reconcile, even after years of consideration.

Though iterations of the story have been retold for centuries—from folktales such as East of the Sun West of the Moon (beautifully retold by Edith Pattou in the lush YA East) to fairy tales like Beauty and the Beast—Lewis threw out romantic love for his exploration of the myth, and refocused the perspective from Pschye to one of her meddling sisters, whose actions Lewis was unable to reconcile, even after years of consideration.

The narrator of Til We Have Faces is Orual, a brave, strong, but disfigured warrior whose love for her sister Psyche outshines her self-admittedly shameful jealousy of the latter’s beauty. In this, Lewis begins exploring a litany of dichotomies: strength versus beauty, fate versus chance, gods versus man.

In fact, Orual’s stated purpose for her narrative is to file a formal complaint to the gods themselves, for, it is partially their fault for disallowing her the ability to see the beautiful castle Psyche had described. Like the jealous sisters of the original myth, Orual demanded Psyche uncover her mate and benefactor because she wanted to protect her sister, and had thought her completely mad. Instead of granting Orual clarity, the Gods punished Psyche, causing her painful trials and tribulations, leaving Orual untouched and wishing badly to die from guilt, shame, and loneliness.

Though the novel was in some ways a 30-plus year study in Apologetics for Lewis, who searched for a way to believe in benevolent gods, for me, it was one of the first times I had felt so badly for such a deeply flawed character. Orual was hateful in ways I could touch and feel and understand, in ways my own love had turned white, hot, and dangerous. Similarly, the application of that love scarred those it touched, much like the lamp oil spilled by Psyche.

I keep the tradition of re-reading Til We Have Faces every year, and have since my early twenties. Each time, more is revealed to me, about life and love and strength and forgiveness, about trust and beauty and what those things really are—both evolving through the years. Like Orual, I continue to learn, continue to be shown, by questioning and reshaping old stories the true wonder of the human experience, and our capacity for narrative imagination.

Camille Griep lives and writes just north of Seattle, Washington. She is the editor of Easy Street and senior editor at The Lascaux Review. Letters to Zell is her first novel. Chat with her on Twitter @camillethegriep.